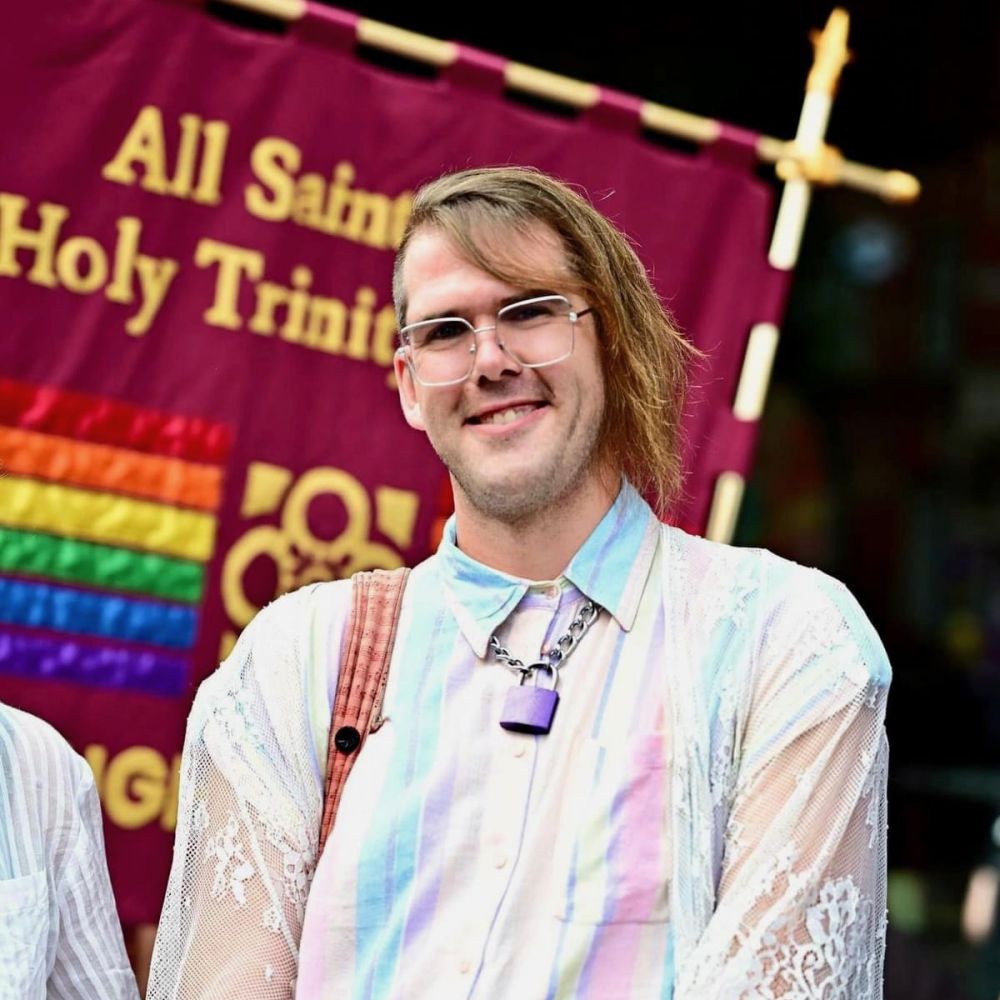

I went on my first-ever Pride March this summer, with a group from All Saints with Holy Trinity Loughborough, under the wider umbrella of inclusive churches in the area.

We arrived at the meeting point to set up our brand new banner, lovingly crafted by Rachael, and joined up with representatives from Leicestershire churches of all denominations. By the time the march set off, we had been directed by the organisers into a parade of around 2,000 people with music, drums and flags keeping us connected up and down the line.

The overall atmosphere was energetic and joyful, with the march ending in Abbey Park with fairground rides, performances and food, but Pride hasn’t always been like that.

In 1969 police raided the Stonewall Inn in New York without a warrant, assaulting the LGBTQ+ patrons, who fought back. A year later the first Pride march took place. Those who marched were protesting the harassment and discrimination they had experienced. They were insisting their city saw and acknowledged them.

Our route felt more like a celebration. It circled Leicester city centre, passing through large numbers of pedestrians spectating or supporting from the crowd. As we wound through the streets, I had some amazing conversations; some really deep and philosophical, others just singing along to the music! I walked with friends, fellow church-goers, complete strangers, people I knew but hadn’t expected to find there, people also at their first Pride event, and others who had been coming for years and seen it evolve since Leicester’s first Pride in 2008.

I also passed other Christians on the sidelines, holding up Bibles and telling us that God loved us (We know. We told them He loved them too) and that we should give our lives to Jesus (We already had; most of us a long time ago!)

It was strange to be faced with a view I used to hold but have since grown beyond. My old views were built on a massively over-simplified view of the world, the Bible, and fearful ideas of what gay people might be like (at the time I barely knew any!)

Many LGBTQ+ people have been hurt by churches. Some Christians reject LGBTQ+ people completely and aggressively. Others of us believe we are welcoming, but then refuse to allow or attend LGBTQ+ weddings, bar them from certain roles, or imply that something is wrong with them that only a miracle can fix. Straight Christians don’t always consider the harm our dismissal causes, because we believe we are righteous to act so callously and fail to see the contradiction in that. To be repeatedly disappointed by this unfair treatment can be devastating to an individual's relationship with their faith.

As a self-proclaimed disciple of Jesus of Nazareth, who famously stalked around a temple, upturning stalls and chasing out livestock, and regularly got into verbal scuffles with the authorities, I have to face the fact that I don’t always live up to his example of practical public action. We may be “saved by grace” (Ephesians 2:8-9) and our belief in Christ, but at the same time “faith without works is dead.” (James 2:26)

Marching is a very public political statement to make. There are worries over whether there will be consequences for attending, such as difficult conversations with friends and family, or being prohibited from certain roles in churches we are part of. But realising this puts you in the shoes of LGBTQ+ people, for whom these worries are a reality. And once a straight Christian has a glimpse of the fear and inequality our siblings in Christ go through, it becomes even harder to stay quietly at home.

I can say that I believe something, but if I never take any action about it, are my words just empty? I can say that I support the right of LGBTQ+ people to marry, live and worship in safety and equality, but if I never demonstrate that in a way that means something to them, how real is my ‘support’?

One of the ways Jesus identified the kingdom of Heaven, was as a place where the oppressed and imprisoned were released (Luke 4:18). The more I learn about LGBTQ+ Christians's experiences of church life, I see the prison we have made. LGBTQ+ Christians have been trapped between needing to be in a church community and the harsh restrictions they must meet to do so; never forming their own families, never finding support in their struggles against discrimination, and maybe never acknowledging their sexuality at all. They have been brave and persistent in showing this needs to change.

By marching, allies make a public statement that we are willing to stand up for LGBTQ+ Christians. They show that we love them as they are, not as second-class citizens who need to change or hide parts of their lives to fully take part in church. And that we are actively working to transform the Church into a place where all people really can worship and find community, without restrictions or barriers.